Doctor Angst & Depression

Although there are multiple factors that make being a modern-day doctor difficult and sometimes frustrating, there are undeniable complexities in today's practices that demand that the medical profession wakes up to a new reality.

Patient safety issues and quality of care are now increasingly demanded not just by healthcare administrators or regulators but also driven by rising patient and public expectations. Our own professional bodies recognise this and are trying to tamp down the sweeping changes that are accruing daily.

Escalating healthcare costs associated with high tech surgeries and medications are forcing healthcare policy makers to scrutinise the need, appropriateness, and quality of healthcare including physician practices, outcomes, including mistakes and avoidable medical errors. Because these invariably add on costs for all payers as well as increase medical litigation.

So like it or not, we just have to live in a new era of greater scrutiny of our work, our standards and quality of care. It's no longer acceptable to simply rely on our 'good' sense of beneficent intentions, that we've done our best as even endorsed by our humdrum run-of-the-mill mediocre peers... We're being held to higher standards that the public and patient can resonate with.

Defective or mis-aligned communications, poor outcome medical care or healthcare-related deaths will no longer be tolerated by more and more patients and their relatives, just as some goods and services are unacceptable if poorly delivered or when bought commercial products fall apart or cannot work or function as expected. So poorer outcomes even if predicted must be clearly defined and kept to a minimum without the appearance of shoddy or dispassionate care along the process...

Like it or not, more patients are asking that the care delivered must match the 'promises' or contractual agreements mutually understood as per informed consent. Medical errors due to poor or defective care would increasingly be seen as not just informed risks that the patient is forced upon to accept. If the results cannot be 'guaranteed' then be prepared for more grievances and complaints and therefore more medico-legal harassment for discovery and negligence/incompetence challenges! Ultimately our professional skills, experience, adequacy of training and maintenance of competency will be asked to show cause and proof, and will be called to answer... Which is why more and more healthcare regulator bodies have been forced to intervene and try to enforce pre-emptively.

Alas, all these expectations are imposing harder and higher standards of competency that if we wish to continue to practice, we must learn to accept or at least help to redefine, as the new paradigm of healthcare for the future. Being gripped by oppressive angst, or immobilised by arm-chair fury, or quiet despair will not help dissipate these challenges! These will come regardless.

Our response should be to address these squarely and collectively to define the issues more agreeably without being overwhelmed by others who might impose even higher professionally-debilitating/constricting standards that could then truly stifle or kill our medical practice altogether!

"It is not now time to talk of aught But chains or conquest, liberty or death" ~ Joseph Addison, in Cato: A Tragedy, Act II, Scene IV

Saturday, December 20, 2014

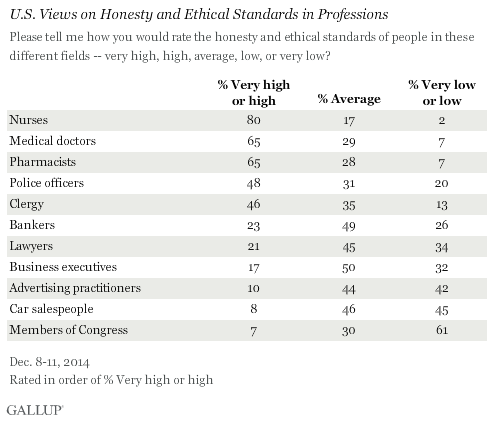

Americans Rate Nurses Highest on Honesty, Ethical Standards.... by Rebecca Riffkin, Gallup

Americans Rate Nurses Highest on Honesty, Ethical Standards

by Rebecca Riffkin

Gallup, Social Issues

Story Highlights

- Nurses continue to be rated the most honest and ethical

- Members of Congress, car salespeople get lowest ratings

- Ratings of bankers and business executives declined this year

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- In 2014, Americans say nurses have the highest honesty and ethical standards. Members of Congress and car salespeople were given the worst ratings among the 11 professions included in this year's poll. Eighty percent of Americans say nurses have "very high" or "high" standards of honesty and ethics, compared with a 7% rating for members of Congress and 8% for car salespeople.

Historically, honesty and ethics ratings for members of Congress have generally not been positive, with the highest rating reaching 25% in 2001. Since 2009, Congress has ranked at or near the bottom of the list, usually tied with other poorly viewed professions like car salespeople and -- when they have been included -- lobbyists, telemarketers, HMO managers, stockbrokers and advertising practitioners.

Although members of Congress and car salespeople have similar percentages rating their honesty and ethics as "very high" or "high," members of Congress are much more likely to receive "low" or "very low" ratings (61%), compared with 45% for car salespeople. Last year, 66% of Americans rated Congress' honesty and ethics "low" or "very low," the worst Gallup has measured for any profession historically.

Other relatively poorly rated professions, including advertising practitioners, lawyers, business executives and bankers are more likely to receive "average" than "low" honesty and ethical ratings. So while several of these professions rank about as low as members of Congress in terms of having high ethics, they are less likely than members of Congress to be viewed as having low ethics.

No Professions Improved in Ratings of High Honesty, Ethics Since 2013

Since 2013, all professions either dropped or stayed the same in the percentage of Americans who said they have high honesty and ethics. The only profession to show a small increase was lawyers, and this rise was small (one percentage point) and within the margin of error. The largest drops were among police officers, pharmacists and business executives. But medical doctors, bankers and advertising practitioners also saw drops.

Bottom Line

Americans continue to rate those in medical professions as having higher honesty and ethical standards than those in most other professions. Nurses have consistently been the top-rated profession -- although doctors and pharmacists also receive high ratings, despite the drops since 2013 in the percentage of Americans who say they have high ethics. The high ratings of medical professions this year is significant after the Ebola outbreak which infected a number of medical professionals both in the U.S. and in West Africa.

At the other end of the spectrum, in recent years, members of Congress have sunk to the same depths as car salespeople and advertising practitioners. However, in one respect, Congress is even worse, given the historically high percentages rating its members' honesty and ethics as being "low" or "very low." And although November's midterm elections did produce a significant change in membership for the new Congress that begins in January, there were also major shakeups in the 2006 and 2010 midterm elections with little improvement in the way Americans viewed the members who serve in that institution.

Previously in 2014, Gallup found that Americans continue to have low confidence in banks, and while Americans continue to have confidence in small businesses, big businesses do not earn a lot of confidence. This may be the result of Americans' views that bankers and business executives do not have high honesty and ethical standards, and the fact that their ratings dropped since last year.

Results for this Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted Dec. 8-11, 2014, with a random sample of 805 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods.

View complete question responses and trends.

Learn more about how Gallup Poll Social Series works.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Doctors Prescribe, Pharmacists Dispense, Patients Suffer .... by Product Of The System

Doctors Prescribe, Pharmacists Dispense, Patients Suffer

Real Life Scenario

Madam Ong is a 52-year-old lady with a twelve-year-history of hypertension and diabetes. She complained of generalised lethargy, lower limb weakness, swelling and pain. She brought along her cocktail of medications for my scrutiny. Her regular medications included the oral antidiabetics metformin and glicazide and the antihypertensives amlodipine and irbesatan. Madam Ong also had a few episodes of joint pains three months ago for which she had seen two other different doctors. The first doctor suspected rheumatoid arthritis and started her on a short course of the potent steroid prednisolone. Thereafter, she developed increasing lower limb swelling for which a third doctor prescribed the powerful diuretic frusemide.

Madam Ong was not on regular follow-up for hypertension and diabetes. Additionally, she has been re-filling her supply of steroids and diuretics at a pharmacy nearby with the purpose of saving up on the consultation charges.

I took a more complete medical history and performed a thorough physical examination. I concluded that this lady’s health was in a complete mess.

She was under sound management by the family physician until the day she defaulted follow up and was started on prednisolone by a doctor who was unaware she was diabetic. The steroid probably helped in relieving her arthritic pains though the suspicion of rheumatoid arthritis was never proven serologically.

However, it also worsened her sugar and blood pressure control and weakened her immune system.

However, it also worsened her sugar and blood pressure control and weakened her immune system.

Her legs swelled up because of the fluid retentive properties of the steroids. In addition, early signs of cellulitis were showing up around her legs due to a weakened immune function. The diuretic prescribed by the third doctor helped a little with the swollen limbs but she became weak from the side effects of diuretics.

Madam Ong’s problems escalated when she decided to forgo her doctors’ opinion altogether and decided to self-medicate simply by collecting all her medications from the pharmacist who supplied them indiscriminately. Unknowingly, the pharmacist had added to the lady’s problems in spite of the wealth of knowledge the pharmacist must have possessed.

The above scenario is a fairly common scene in the Malaysian healthcare. We see here an anthology of errors initiated by doctors, propagated by the patient’s health seeking behavior and perpetuated by a pharmacist.

Noteworthy but Untimely Move

The Ministry of Health is set to draw a dividing line between the physician’s role and the pharmacist’s, restricting physicians to prescribing and according dispensing rights solely to the pharmacists.

Such a move virtually has its effects only upon doctors in the private practice and particularly the general practitioner who relies on prescription sales for much of one’s revenue.

Doctors prescribe and pharmacists dispense. It’s the international role of each profession and very much the standard practice in most developed countries.

The Ministry of Health however, has failed to take into account the local circumstances in mooting this inaugural move in Malaysian healthcare. The logic and motive behind the Ministry of Health’s proposal is in fact laudable, but only if the Malaysian healthcare scenario is more organized and well-planned.

Spiraling Healthcare Costs

In the United Kingdom, all costs are borne by the National Healthcare Services. In the United States, despite all the negativity painted by Michael Moore’s Sicko, most fees are paid for by health insurance without which one cannot seek treatment. In these countries and many European nations, there is hardly any out-of-pocket monetary exchange between patients and their clinicians.

This however is not the case for Malaysia. Most patients who visit a private clinic are self-paying clients. The costs of consultation and medications are real and immediately tangible to patients. A visit to the general clinic for a simple upper respiratory tract infection may set one back by as much as RM 50.00 inclusive of consultation and medication. Most clinics these days are charging reasonable sums between RM 5 to RM 15 for consultation. Some are even omitting consultation charges altogether in view of the rising costs of basic healthcare. The introduction of the MOH’s ‘original seal’ to prevent forgery of drugs contributed much to this.

There is no denial that most clinics rely on the sales of medications in order to remain financially viable. From my personal experience, the charges for medications by private clinics are not necessarily higher than pharmacies. In fact, since each practitioner has a stockpile of one’s own preferred drugs, the cost price of the medications can be much lower than that obtained by the pharmacists who need to stockpile a wide variety of drugs. It is therefore a misconception that pharmacies will provide medications to patients at a much lower cost all the time for all medications.

Retracting dispensing privileges from the private clinics will only force practitioners to charge higher consultation fees in order to sustain viability of their practices. In the end, the patients end up paying a greater cost for the same quality of healthcare and medications. Inevitably, much of the increase in healthcare costs will also be passed on panel companies who will then be paying two professionals for the healthcare of their employees.

In this season of spiraling inflation, this proposal by the Ministry of Health is ill-time and poorly conceived.

Unequal Distribution of Medical and Pharmacy Services

As it already is, private general practice clinics are mushrooming at an uncontrolled rate. A block of shoplots in Kuala Lumpur may house up to five clinics. Does Malaysia have a corresponding number of pharmacists to match the proliferating medical clinics? If and when clinics are disallowed to dispense medications, the market scenario will become one that heavily favors pharmacists. The struggling family physician suddenly loses a significant portion of his revenue while the pharmacist receives a durian runtuh overnight.

The situation is worst in the less affluent areas and rural districts where the humble family physician may be the solitary doctor within a 50km radius and no pharmacy outlets at all. For example, there are no pharmacies in Kota Marudu, Sabah and only one in the town of Kudat. Patients seeking treatment in these places will get a consultation but have no avenue to collect their prescription if doctors lose their dispensing privileges.

The absence and dearth of 24-hour pharmacies is also a pertinent issue. At present, many clinics operate around the clock to provide immediate treatment for patients with minor systemic upset. These clinics play an important role in reducing the crowd size and the long waiting hours at the emergency departments of general hospitals.

Without a corresponding number of 24-hour pharmacies to dispense urgent medications, the role of 24-hour clinics will be obtunded. The MOH’s plans of implementing its doctors-prescribe-pharmacists-dispense policy will merely backfire and result in the denial of services to patients.

A Bigger Problem Is The System Itself

The increasing number of medical centers around the country is not necessarily in the patients’ best interests or an indicator of improved healthcare provision. Most clinics and medical centers serve an overlapping population of patients. A person may be under a few different clinics simultaneously for his chronic multiple medical problems, resulting in a scattered, interrupted medical record. One doctor may not be informed of the interventions and medications undertaken by the patient at another practice. The concept of continuous care and a long term doctor-patient relationship is practically improbable.

This is unlike the system in the United Kingdom where each family physician is allotted a certain cohort of patients for long term care. The doctor remains in full knowledge over his patients’ progress, making general practice one that is rewarding and meaningful.

The trouble-ridden Malaysian healthcare system prevents optimal clinical practice especially for doctors in the private sector.

Until the Ministry of Heath puts in place a more systematic and organized approach to healthcare, patients will still be denied optimal medical services despite a clear division between the roles of doctors and pharmacists. The process of prescribing and dispensing is but one step in the cascade of events that may result in harm being done to the patient. Role separation between the doctor and the pharmacist will not eliminate drug-related malpractice and negligence, as I have illustrated in the real clinical scenario above.

Loss of Clinical Autonomy

Private practitioners in Malaysia are at present enjoying a reasonable sense of autonomy over the health of their patients. In many ways, the freedom of clinicians to make decisions with adequate knowledge of the patient’s needs and circumstances is a plus point in clinical practice.

Involving the pharmacists in the daily management of every patient removes a great part of the doctor’s control over the clinical circumstances of the patient. He may prescribe one drug only to be overruled by the dispensing pharmacist later. The clinician has privy to much information about the patient’s circumstances that are available only in the patient’s medical records. It is based on this information that a clinician makes decisions on the final choices of medications for the patient.

A dispensing pharmacist does not have access to such priceless clinical history and may very well make ill-informed decisions in the patient’s medications. Once again, my introductory scenario demonstrates how pharmacists can help perpetuate a patient’s mismanagement.

Selective Implementation of Rules

Rules in any game should be fair and just and implemented on both parties. If doctors are to be prohibited from dispensing, shouldn’t pharmacists too be forbidden from diagnosing, examining, investigating and prescribing?

Yet this is exactly what takes place everyday in a typical pharmacy.

I have seen with my own eyes (not that I can see with someone else’s eyes anyway) pharmacists giving a medical consultation, performing a physical examination and thereafter recommending medications to walk-in customers. It is also not uncommon to find pharmacies collaborating with biochemical laboratories to conduct blood tests especially those in the form of seemingly value-for money ‘packages’. These would usually include a barrage of unnecessary tests comprising tumor markers, rheumatoid factor and thyroid function tests for an otherwise well and asymptomatic patient.

Pharmacists intrude into the physicians’ territory when they begin to do all this and more.

Doctors may occasionally make mistakes due to their supposedly inferior knowledge of drugs despite the fact that they are trained in clinical pharmacology.

In the same vein, pharmacists may have studied the basic features of disease entities and clinical biochemistry but they are nonetheless not of sufficient competency to diagnose, examine, investigate and treat patients. Pharmacists are not adequately trained to take a complete and thorough medical history or to recognize the subtle clinical signs so imperative in the art of differential diagnosis.

In more ways than one and increasingly so, pharmacists are overtaking the role of a clinical doctor. Patients have reported buying antibiotics and prescription drugs over the pharmacy counter without prior consultation with a physician.

If the MOH is sincere to reduce adverse pharmacological reactions due to supposedly inept medical doctors, then it should also clamp down on pharmacists playing doctor everyday in their pharmaceutical premises. Patients will receive better healthcare services only when each team member abides by and operate within their jurisdiction.

The move to restrict doctors to prescribing only while conveniently ignoring the shortcomings and excesses among the pharmacy profession is biased and favors the pharmacists’ interests.

The Root Problem is Quality

A significant issue in Malaysian healthcare is that of the quality of our medical personnel. This includes doctors, dentists, nurses and pharmacists, therapists, amongst others. A substantial number of our doctors are locally trained and educated. If current trends are extrapolated to the future, the number of local medical graduates is bound to rise exponentially alongside the unrestrained establishment of new medical schools.

The quality and competency of current and future medical graduates produced locally is an imperative point to consider. Competent doctors with a sound knowledge of pharmacology will go a long way in improving patient care and minimizing incidence of adverse drug reactions. The very fact that the MOH resorts to the drastic step in prohibiting doctors from dispensing medications indicates that it must be aware of the high prevalence of drug-related clinical errors.

Much of patient safety revolves around the competency of Malaysian doctors in making the right diagnosis and prescribing the right medications. Retracting dispensing rights from clinicians therefore, will not solve the underlying problem. Our doctors might still be issuing the right medications but for the wrong diagnosis. In the end, a dispensing pharmacists will still end up supplying the patient with a medication of the right dosage, right frequency but for the wrong indication.

Patient safety therefore begins with the production of competent medical graduates. The problem lies in the fact the same universities producing medical doctors are usually the same institutions producing pharmacists. It is really not surprising, since the basic sciences of both disciplines are quite similar. Therefore, if the doctors produced by our local institutions are apparently not up to par, can we expect the pharmacy graduates who learnt under the same teachers to be much better in their own right?

Among other remedial measures, my personal opinion is that the medical syllabus of our local universities is in desperate need for a radical review. There is a pressing need for a greater emphasis on basic and clinical pharmacology. At the same time, the excessive weightage accorded to paraclinical subjects like public health and behavioral medicine need to be trimmed down to its rightful size. Lastly, genuine meritocracy in terms of student intake, as opposed to ‘meritocracy in the Malaysian mould’, will drastically improve the final products of our local institutions.

The MOH’s Own Backyard Needs Cleaning

Healthcare provision in Malaysia has undergone radical waves of change during the Chua Soi Lek era. The most sweeping changes seem to affect the private sector much more than anything else. The Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act typifies MOH’s obsession with regulating private medical practice as though all doctors are under MOH’s ownership and leash.

An analyst new to Malaysian healthcare might be forgiven for having the impression that the Malaysian Ministry of Health is currently on a witch hunt in order to make private practice unappealing and unfeasible in order to reduce the number of government doctors resigning from the civil service.

Regardless of MOH’s genuine motives, it must be borne in mind that private healthcare facilities only serve an estimated twenty percent of the total patient load in the whole country. The major provider of affordable healthcare is still the Ministry of Health and probably always will be. Targeting private healthcare providers therefore, will only create changes to a small portion of the population. Overhauling the public healthcare services conversely, will improve the lot of the remaining eighty percent of the population.

At present, the healthcare services provided by the Malaysian Ministry of Health is admittedly among the most accessible in the world. The quality of MOH’s services however, leaves much to be desired. Instead of conceiving ways and means to make the private sector increasingly unappealing to the frustrated government doctor, the MOH needs to plug the brain drain by making the ministry a more rewarding organization to work in.

The MOH needs to clean up its own messy backyard before encroaching into the private practitioners’.

An indepth analysis of MOH’s deficiencies I’m afraid, is not possible in this article.

MOH’s “To Do List”

The prescribing-dispensing issue should hardly be MOH’s priorities at the moment.

I can effortlessly think of a list of issues for the MOH to tackle apart from retracting the right of clinicians to dispense drugs.

Private laboratories are conducting endless unnecessary tests upon patients and usually at high financial cost despite their so-called attractive packages. In the process, patients are parting with their hard-earned money for investigations that bring little benefit to their overall well being. Mildly ‘abnormal’ results with little clinical significance result in undue anxiety to patients. More often than not, such tests will result in further unnecessary investigations. The MOH needs to regulate the activities of these increasingly brazen and devious laboratories.

Medical assistants trained and produced by the MOH’s own grounds are running loose and roaming into territories that are far beyond their expertise. It is not uncommon to find patients who were on long term follow up under a medical assistant for supposedly minor ailments like refractory gastritis and chronic sorethroat. A few patients with such symptoms turned up having advanced cancer of the stomach and esophagus instead. The medical assistants who for years were treating them with antacids and multiple courses of antibiotics failed to notice the warning signs and red flags of an occult malignancy. They were not trained in the art of diagnosis and clinical examination but were performing the tasks and duties of a doctor. There is no doubt that the role of the medical assistant is indispensable in the MOH. Just as a surgeon would not interfere with the role of an oncologist, medical assistants too must be aware of the limits of their expertise. MOH will do well to remember the case of the medical assistant caught running a full-fledge surgical clinic in Shah Alam in late 2006.

Adulterated drugs with genuine risks of lethal effects are paddled openly in road side stalls and night markets. They are extremely popular among folks from all strata of society who rarely admit to the use of such toxins to their physicians. It is possible and highly probable that many unexplained deaths taking place each day are in some way related to the rampant use of such preparations.

Non-medical personnel are performing risky and potentially lethal procedures daily without the fear of being nabbed by the authorities. These are mostly aesthetic procedures. Mole removals, botulinum toxin injections and even blepharoplasty are carried out brazenly by unskilled personnel and usually in the least sterile conditions. It makes a mockery of the plastic surgeon’s years of training but above all, proves that the MOH is indeed barking up the wrong tree in its obsession to retract the dispensing privileges of medical practitioners.

Closing Points

In summary, a patient’s health is affected by many factors – a doctor’s aptitude is merely one step in a torrent of events. The health seeking behaviors of patients play an imperative role in the final outcome of one’s own health. Most harm to patients can only occur as a result of unidentified minor errors in the management flowchart of a patient. If allowed to accumulate, such errors converge as a snowball that threatens the long term outcome of an ill person.

There are a multitude of other clinical errors apart from prescribing and dispensing, some of which are not at all committed by trained medical staff. The MOH must get its priorities right by first overhauling an increasingly overloaded public healthcare service.

Lastly, the difference between a drug and a poison is the dose. A toxin used in the right amount for the right condition is an elixir. A medication used in the wrong dosage and for the wrong indication is lethal poison.

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

APHM warns cost of private healthcare will rise... By Melissa Annabelle Lawson

APHM warns cost of private healthcare will rise

PETALING JAYA: The Association of Private Hospitals of Malaysia (APHM) has warned that the cost of private healthcare will experience at least 5% increase starting from April 1 next year due to the Goods and Services Tax (GST) coming into force.

Speaking at a conference today, APHM president Datuk Dr Jacob Thomas said private hospital doctors are independent practitioners who work in the hospitals on a contract basis and are not employees unlike medical officers in public hospitals.

He said imposing the consumption tax on their services will only lead to patients having to dig deeper into their pockets.

"We have repeatedly consulted the Ministry of Finance and the Customs Department to appeal for health care services to be regarded as Exempt Supply but we were rejected. Instead, it was suggested that the hospital absorbs the additional cost but this is hardly a feasible option and will lead to small hospitals going bankrupt," he added.

He said that this was contrary to Health Minister Datuk Seri S. Subramaniam's assurance on Nov 3 that GST would not impact healthcare cost.

Jacob stressed that with the implementation of GST, hospital operational costs such as security, laundry and housekeeping services will increase and this will inevitably be borne by the patients who use them.

He also said that there were conflicting statements on whether GST would be implemented on drugs and medical equipment.

"There have been 5 different updated guidelines in the past two months. We are still waiting for the list on equipment that are exempted from GST," he said.

"Around 45-70% of a patient's medical bill, depending on the medical procedure involved, is the doctor's portion and thus when the doctor's fee and medication increase, we can predict a big shift of patients from the private sector to the public sector," Jacob said, adding that this would subsequently clog up the public healthcare system.

"If the policy on private healthcare services cannot be revised, we ask that the Government stop giving false assurances about GST not impacting the cost and instead, tell them the truth. This is to avoid the mismatch between the perception of the public, government's intention and implementation by the industry," he stressed.

In addition to rising private healthcare cost, Jacob said insurance premiums would also be affected although he could not determine the extent.

"Some 13% of the country's healthcare is in the private sector. The country's private sector ranks third in the world. It will be challenging to maintain such an achievement if prices shoot up."

Jacob said that the price increase would affect everyone as private healthcare is not limited to a certain social class.

"Doctors in the government hospitals also refer their patients to private hospitals for certain procedure,." he elaborated.

Copyright © 2014 Sun Media Corporation Sdn. Bhd.

See more at: http://m.thesundaily.my/node/

Doctors Are Fighting With Their MBA Bosses... By Natalie Kitroeff

Doctors Are Fighting With Their MBA Bosses

By Natalie Kitroeff

Businessweek: July 31, 2014 3:16 PM EDT

Tensions between physicians and the business school types managing them have brewed for years, as health care shifted toward relying on business people rather than clinicians to run medical centers. Now the strains are beginning to creep into public view. It can get ugly.

In Australia, outrage among a doctors’ group erupted this spring after a coroner’s investigation into the suicide of a young girl suggested that medical mismanagement was a factor in her death.

Some 20 psychiatrists signed an open letter protesting the lack of a physician-led governance structure in the hospital system, according to a report in the Australian Medical Association’s magazine. Following the coroner’s inquiry, a doctors’ trade group sent a letter to the government demanding that the hospital system in question incorporate more psychiatrists in its leadership and throughout its ranks.

The incident is an extreme example of more common tensions over practices often favored by those trained in management rather than medicine.

Experts say disagreements between clinicians and managers, over such things as paying doctors based on their performance, are cropping up in hospitals across the globe. Some industry insiders fear that patients may bear the brunt of the fallout.

“It’s as if the patient’s a pawn in this struggle for influence and control between physicians and nonphysicians,” says Todd Kislak, a Harvard MBA who worked for nearly a decade as a senior manager in a physician group.

The business of health care is roaring—especially for nondoctors. Jobs in the industry increased 75 percent from 1990 to 2012, but the vast majority of new positions didn’t go to M.D.s, according to an analysis published last year in the Harvard Business Review. Today, the field counts 10 managers and managers’ helpers for every one doctor.

Doctors’ offices hold an uncomplicated allure for MBA students. The health-care industry has been good to students of business, handing out consistently reliable job offers and among the highest raises of any profession, according to a survey by the Graduate Management Admissions Council. One in every 20 B-School graduates goes into health care, according to GMAC.

That trend does not sit well with some medical practitioners.

“Physicians may have their faults and problems, but every one of us swore an oath at some point that we would put your interests as patients ahead of everything else,” says Roy Poses, a professor of medicine at Brown University’s Alpert Medical School, adding that executives tend to put revenue first.

“If I have to work as a physician for managers like that, they may push me to do what will make them a lot more money fast, even if this would be useless, or even harmful to you as a patient.”

Hospitals run by so-called professional managers have chief executives without clinical experience or a degree in medicine. A 2009 study showed that trained physicians are the leading administrators in just 4 percent of hospitals in the U.S.

Recent research casts some doubt on whether the influx of card-carrying managers has been good for the health of Health Inc. In a 2011 performance review of roughly 300 hospitals, Amanda Goodall, a professor at City University’s Cass Business School in London, found that the ones led by physicians were ranked 25 percent higher than the average hospital. Another study, released last year, showed that hospital systems in England with more clinicians in the boardroom had lower death rates.

“Leadership positions should be held by people who have the core business expertise,” Goodall says, a description that she said doesn’t fit people who are versed in managing people rather than treating them.

Not all physicians want to be bureaucrats, however. Getting doctors to volunteer for top jobs can be stymied by their natural aversion to the C-suite jungle, Goodall says. Professional managers have “created a world in which they can live in quite happily. But that world, to a large extent, excludes the experts.”

That may change as students of medicine begin to learn about the business world. Educators have gradually warmed to the idea of teaching med students at least some of what it takes to run a business, and now more than half of all medical schools offer a joint M.D./MBA program, according to a study in the peer-reviewed Physician Executive Journal.

Making hospitals run well for patients isn’t as simple as kicking out the MBAs, however. Most agree that managers bring a crucial set of skills to health care. “Being an expert isn’t a proxy for having leadership experience and management expertise,” Goodall says.

Todd Kislak, the former hospital manager, says that doctors often “don’t have the understanding of economics finance accounting” to administer giant health-care organizations efficiently. “Hospitals are a business, and they’re also a place of caregiving.”

The only way to eliminate the tension between the businesspeople who run hospitals and the doctors who work in them is to merge the two tribes, Kislak says.

“The coats vs. the suits,” he says. “What you need is people who can wear both.”

By Natalie Kitroeff

Businessweek: July 31, 2014 3:16 PM EDT

Tensions between physicians and the business school types managing them have brewed for years, as health care shifted toward relying on business people rather than clinicians to run medical centers. Now the strains are beginning to creep into public view. It can get ugly.

In Australia, outrage among a doctors’ group erupted this spring after a coroner’s investigation into the suicide of a young girl suggested that medical mismanagement was a factor in her death.

Some 20 psychiatrists signed an open letter protesting the lack of a physician-led governance structure in the hospital system, according to a report in the Australian Medical Association’s magazine. Following the coroner’s inquiry, a doctors’ trade group sent a letter to the government demanding that the hospital system in question incorporate more psychiatrists in its leadership and throughout its ranks.

The incident is an extreme example of more common tensions over practices often favored by those trained in management rather than medicine.

Experts say disagreements between clinicians and managers, over such things as paying doctors based on their performance, are cropping up in hospitals across the globe. Some industry insiders fear that patients may bear the brunt of the fallout.

“It’s as if the patient’s a pawn in this struggle for influence and control between physicians and nonphysicians,” says Todd Kislak, a Harvard MBA who worked for nearly a decade as a senior manager in a physician group.

The business of health care is roaring—especially for nondoctors. Jobs in the industry increased 75 percent from 1990 to 2012, but the vast majority of new positions didn’t go to M.D.s, according to an analysis published last year in the Harvard Business Review. Today, the field counts 10 managers and managers’ helpers for every one doctor.

Doctors’ offices hold an uncomplicated allure for MBA students. The health-care industry has been good to students of business, handing out consistently reliable job offers and among the highest raises of any profession, according to a survey by the Graduate Management Admissions Council. One in every 20 B-School graduates goes into health care, according to GMAC.

That trend does not sit well with some medical practitioners.

“Physicians may have their faults and problems, but every one of us swore an oath at some point that we would put your interests as patients ahead of everything else,” says Roy Poses, a professor of medicine at Brown University’s Alpert Medical School, adding that executives tend to put revenue first.

“If I have to work as a physician for managers like that, they may push me to do what will make them a lot more money fast, even if this would be useless, or even harmful to you as a patient.”

Hospitals run by so-called professional managers have chief executives without clinical experience or a degree in medicine. A 2009 study showed that trained physicians are the leading administrators in just 4 percent of hospitals in the U.S.

Recent research casts some doubt on whether the influx of card-carrying managers has been good for the health of Health Inc. In a 2011 performance review of roughly 300 hospitals, Amanda Goodall, a professor at City University’s Cass Business School in London, found that the ones led by physicians were ranked 25 percent higher than the average hospital. Another study, released last year, showed that hospital systems in England with more clinicians in the boardroom had lower death rates.

“Leadership positions should be held by people who have the core business expertise,” Goodall says, a description that she said doesn’t fit people who are versed in managing people rather than treating them.

Not all physicians want to be bureaucrats, however. Getting doctors to volunteer for top jobs can be stymied by their natural aversion to the C-suite jungle, Goodall says. Professional managers have “created a world in which they can live in quite happily. But that world, to a large extent, excludes the experts.”

That may change as students of medicine begin to learn about the business world. Educators have gradually warmed to the idea of teaching med students at least some of what it takes to run a business, and now more than half of all medical schools offer a joint M.D./MBA program, according to a study in the peer-reviewed Physician Executive Journal.

Making hospitals run well for patients isn’t as simple as kicking out the MBAs, however. Most agree that managers bring a crucial set of skills to health care. “Being an expert isn’t a proxy for having leadership experience and management expertise,” Goodall says.

Todd Kislak, the former hospital manager, says that doctors often “don’t have the understanding of economics finance accounting” to administer giant health-care organizations efficiently. “Hospitals are a business, and they’re also a place of caregiving.”

The only way to eliminate the tension between the businesspeople who run hospitals and the doctors who work in them is to merge the two tribes, Kislak says.

“The coats vs. the suits,” he says. “What you need is people who can wear both.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)